Iran

Shahin Shahr, Iran, July 2001. Mother and daughter during social visit. Mère et sa fille recevant des invités.

“Women didn’t simply dress up at private Tehran parties: They dressed and danced and flirted to the nines — in slinky black-satin numbers and under layers of makeup. Parties were not just parties, they were feasts of forbidden fruit. How dull, how unfulfilling, an American suburb must be in comparison!”

The Ends of the Earth, Robert Kaplan, 1996.

Isfahani mother and daughter entertaining guests at home. The social scene is paramount, taking precedence over any business, being business in itself, visits to relatives, to friends, to superiors, are an absolute priority, observing an elaborate and strict etiquette, from the minute-long greetings to the serving of mounds of fruits, nuts, sweets, nabat, and cup after cup of tea, to the subtle details of the chadors. And Kaplan is right, the chador is actually a very useful garment, for women can hide anything under it, a flashing miniskirt or worn-out jeans, a burning passion or a casual indifference, and it does shield women from unsolicited “attention”. In New York, a radiating girlfriend got a downright insulting “Can I eat your pussy?” on Amsterdam Avenue. Mind you, while on an internship in Madrid, a professional colleague had abruptly asked her, “May I fuck you?”… In Greece, a friend of mine married to an Iranian woman, tired of seeing exhibited, on billboards, in magazines, or in the street, increasingly bared women, exploded, “I prefer to see them covered than underdressed!” Neither society leaves you with a choice.

“Les femmes ne s’habillaient pas tout simplement lors de soirées privées à Téhéran: elles s’habillaient, dansaient et flirtaient à fond – dans des habits de satin noir et sous des couches de maquillage. Les fêtes n’étaient pas seulement des fêtes, c’étaient des fêtes de fruits interdits. Combien terne, combien peu satisfaisant, une banlieue étatsunienne est par comparaison! ” The Ends of the Earth, Robert Kaplan, 1996.

Shahin Shahr, Iran, July 2001. Women clap as men dance. Les femmes battent le rythme pour leurs hommes qui, eux seuls, dansent.

Isfahan, Iran, September 1994. Masjed-é Jâme mosque.

“And above all is the blue. We must come all the way here to discover the blue. In the Balkans already, the eye gets ready; in Greece, it commands but self-importantly: an aggressive blue, restless like the sea, it still lets affirmation, projects, a kind of intransigence, filter through it. While here!… The shops’ doors, the horses’ halters, the cheap jewelry: everywhere is this inimitable Persian blue which lightens the heart, which holds Iran so closely, which lights up and gets a patina with time just like a great painter’s palette lights up”. L’usage du monde, Nicolas Bouvier, 1963 (1953-54 travel)

A whirl of chadors by Masjed-é Jâme mosque, a true museum of 11th to 18th century Islamic art. It is not the cowl that makes the monk. In the mullah’s Iran, the compulsory black cover for the women is more superficial than in neighboring countries, such as Pakistan or Turkey, where it is the sign of a firm religious devotion.

“Et surtout il y a le bleu. Il faut venir jusqu’ici pour découvrir le bleu. Dans les Balkans déjà, l’oeil s’y prépare; en Grèce, il domine mais il fait l’important: un bleu agressif, remuant comme la mer, qui laisse encore percer l’affirmation, les projets, une sorte d’intransigeance. Tandis qu’ici! Les portes des boutiques, les licous des chevaux, les bijoux de quatre sous: partout cet inimitable bleu persan qui allège le coeur, qui tient l’Iran bout de bras, qui s’est éclairé et patiné avec le temps comme s’éclaire la palette d’un grand peintre”. L’usage du monde, Nicolas Bouvier, 1963 (voyage en 1953-54)

Tourbillon de chadors devant la mosquée Masjed-é Jâme, véritable musée de styles islamiques du 11ème au 18ème siècles. L’habit ne fait pas le moine et dans l’Iran des imams, l’enveloppe noire qui recouvre obligatoirement les femmes est plus superficielle que dans les pays voisins, comme le Pakistan ou l’Arabie Séoudite, où elle constitue une ferme affirmation de sa foi ou celle de sa famille.

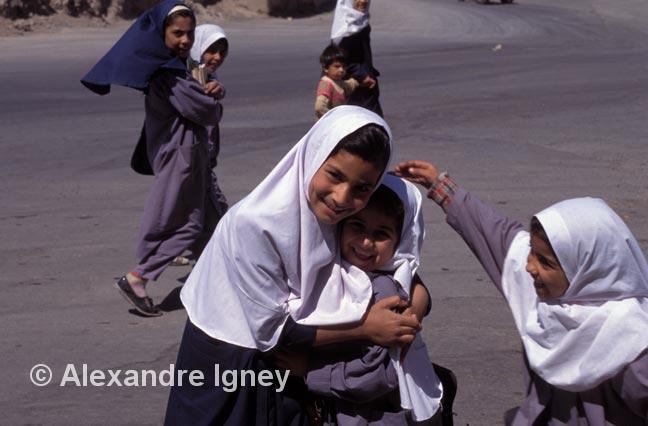

Bam, Iran, September 1994. Schoolgirls in front of old citadel. A la sortie de l’école..

Contrary to what one might think by seeing their dress, a more brilliant future awaits these schoolgirls than in neighboring countries. In Iran we found women in all venues of society and the economy. We saw them driving cars or motorbikes, unlike Saudi Arabia where they are prohibited from driving, at bank or public offices management desks, in restaurants or tea rooms unlike Greek cafés where the male element dominates, they answer you very lively when you talk to them and easily let themselves be photographed unlike Morocco where they throw stones at you, they never hide their face under a clothed grid — the borquas — unlike Pakistan where they even eat behind it, they welcome you at home and eat at your “table” — on the floor — without hiding in the “women’s room”, i.e. the kitchen, unlike Egypt where the man brings the dishes to the guests. And in the street, they let a curl of dyed hair, a piece of jewelry, the bottom of designer pants, show from under the chador, unlike Libya where the rare female passer-by walks wrapped in a large, white bed-sheet.

Contrairement à ce que leur aspect recouvert laisse croire à première vue, un avenir plus brillant attend ces écolières que leurs coreligionnaires des pays voisins et moins voisins. En Iran on rencontre des femmes partout et dans tous les rôles de la société et de l’économie. On les voit au volant des voitures ou sur des motos pas comme en Arabie Séoudite où elles sont interdites de conduire, derrière les bureaux de banque ou de l’administration, au restaurant ou dans des salons de thé pas comme dans les cafés grecs où domine l’élément mâle, elles vous répondent vivement quand vous leur parlez et se laissent photographier pas comme au Maroc où on vous lance des pierres, elles se cachent très rarement le visage sous un voile grillagé pas comme au Pakistan où elles vont jusqu’à manger sous ce masque de tissu, elles vous accueillent chez elles et mangent à votre “table” — généralement à même le sol — sans se retirer dans la “pièce pour femmes”, la cuisine, pas comme en Egypte où c’est même l’homme qui apporte les plats. Et dans la rue, elles laissent s’échapper de leur chador une boucle de cheveux teints, un bijou, un bas de pantalon designer, pas comme en Libye où les rares passantes circulent enveloppées d’un vaste drap de lit blanc.

Bam, Iran, September 1994. Afghan refugees rehabilitate the old citadel (that was, obviously, before the terrible 2003 earthquake). Des réfugiés afghans réparent l’ancienne citadelle.

Two Afghanis — out of a million refugees in Iran — renovating the old Sassanid-Safavid citadel. We continued eastwards, to the meeting-point of an Afghanistan in full fratricidal war, a Pakistan king of contraband, and an Iran of revolutionary guards. The Lonely Planet guide warns: “The Komité presence throughout the province is extremely heavy, occasionally even intimidating”. The bus left us at 1 am in Zahedan, and my companion and I had no other choice but to hop into an old taxi to cover the 100 or so kilometers to the Pakistani border (1 dollar/person). On the way, a patrol of revolutionary guards did indeed stop us and asked us to… please help them push, under the moonlight, their pick-up which had gotten bogged in the sands. When we reached the village of Mirjaveh, we knocked at the gate of what we thought was the border-post, and were sheltered in a yard — with blankets smelling of dog. In the morning, we realized we were in the barracks of the revolutionary guards who brought us breakfast — pita bread, white cheese, and tea — while cracking countless jokes, then drove us to the real border-post, a few kilometers away… There, the chador-clad official interrupted our passports check to chase her 3-year old who had slipped out the open door.

Deux parmi le million de réfugiés afghans en Iran, oeuvrent la rénovation de l’ancienne citadelle sassanide (3e-7e)-safavide (16e-18e siècles). Quant nous, nous avons continué vers le point névralgique où s’unissent l’Afghanistan en pleine guerre fratricide, le Pakistan de la contrebande et l’Iran des gardes révolutionnaires. Le guide de voyage Lonely Planet met en garde contre ces derniers: “The Komité presence throughout the province is extremely heavy, occasionally even intimidating”. En la compagnie d’un Japonais, ma compagne et moi avons dû quitter Zahedan où le bus nous avaient laissés une heure du matin, dans un vieux taxi pour parcourir la centaine de kilomètres jusqu’à la frontière pakistanaise (coût: 1 dollar/personne). En chemin, une patrouille de gardes révolutionnaires nous ont arrêtés pour… nous demander de les aider pousser, sous le clair de lune, leur pick-up hors des sables où il s’était enlisé. Arrivés au village de Mirjaveh, nous avons frappé la grille de ce que nous pensions être le poste-frontière, et été hébergés dans la cour — avec couvertures — de ce qui s’est révélé le matin être la caserne des gardes révolutionnaires lesquels, nous ont offert par-dessus le marché le petit déjeuner — galettes, fromage blanc et thé — et ensuite conduits jusqu’au véritable poste-frontière à quelques kilomètres de là.

Sheikh Ali Khan, Iran, October 2000. Woman weaving in a Zagros mountain village. All men have left for Kuwait on job contracts. Une femme tisse dans un village isolé de la chaine du Zagros. Tous les hommes sont partis au Koweit pour du travail.